Native Plant Ranges and Climate Change

Climate change is shifting temperatures around the world away from their historical ranges. Rapid shifts in the yearly winter freezing and peak summer temperatures is a huge issue for both humans and natural ecosystems. These changes can be especially hard for the native plants, which often thrive only within a particular temperature range. Planting natives can be an important part of creating a climate-resilient landscape, but changing temperatures can endanger the health of the plants and the environmental benefits they provide.

Native Plants

According to the USDA, native plants are “a part of the balance of nature that has developed over hundreds or thousands of years in a particular region or ecosystem.” Native plants in the U.S. are only those that existed pre-European settlement. Non-native plants can be introduced from a variety of sources, from birds, ship ballast water, or most often by people. Many of the most dangerous and quick-spreading non-natives are labeled as invasive plants and noxious weeds.

Native plants are incredibly important for a healthy and diverse environment. They provide habitat and food for local wildlife and are better than non-natives for bees and other insects. Native plants also have a role in lessening the impacts of climate change and severe weather. They are usually better at trapping carbon than any non-native alternative. Planting drought-resistant native plants can also help reduce water use, mitigate climate change damage to your property, and reduce the urban heat island effect. Unfortunately, the vast majority of landscaping plants and flowers available in nurseries are non-native, and often invasive.

Climate Change and Hardiness Zones

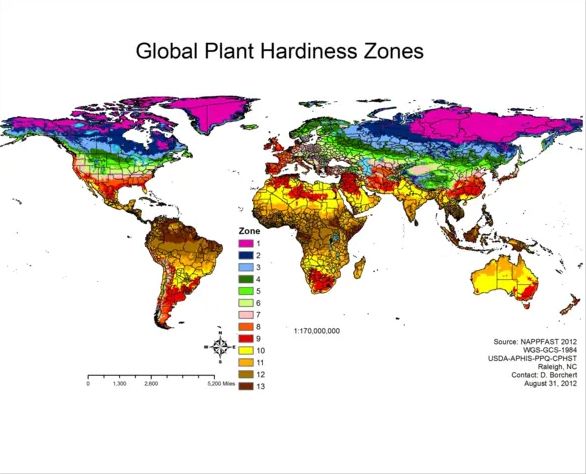

A warming climate is changing the range of temperatures that native plants are used to. Scientists describe this shift using the terminology of “hardiness zones”:

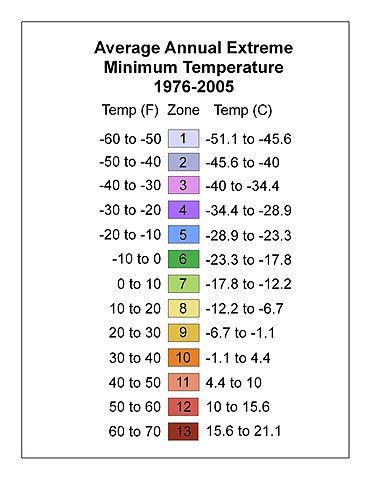

- Hardiness Zone: A hardiness zone describes a geographic range that is defined by a certain range of annual minimum temperature. Hardiness zones are measured by the USDA by average annual minimum winter temperature and are divided by intervals of 10 degrees Fahrenheit.

Studies predict that future climate warming scenarios will cause hardiness zones to shift northward by 13 miles every decade. This is a dramatic change for the health and survival of plants, especially for the cultivation of cold-intolerant perennial agriculture such as almond, kiwi, and orange crops.

Impacts of Shifting Hardiness Zones

Shifting hardiness zones is causing the migration of plants and animals northward and to higher altitude regions. However, climate scientists warn that this migration is not happening at the same rate; a tree could be moving locations more gradually than the birds that rely on the fruit the tree produces. This phenomenon is causing the breakdown of ecosystems, especially in cases where geographical boundaries (like seas and mountain ranges) prevent native plants from shifting naturally to more suitable climate regions. Reintegration efforts for native and endangered plants often take into account the rate of habitat repositioning when deciding where to plant.

Struggling native plants will have a wide impact on our environments, economy and health. Disruptions to existing agricultural industries are already causing the need for quick adaptations to find viable crops. For example, farmers in Costa Rica are now growing oranges instead of coffee.

Conclusion

Planting native plants is a huge benefit for the health of your environment. But with changing climates, many plants are no longer suited to the climate of the geographical area they are native to. The question of where and how to reintroduce natives into local habitats is becoming more difficult.