California and the Pacific Northwest are experiencing unprecedented wildfires. The severity, location, and timing of these fires are extreme outlier events that match the exceptional year that is 2020. Therein lies the problem. When you think about what to do next, whether it’s rebuilding, remodeling, moving, reinsuring, offering a new mortgage, or any of the more collective decisions such as wildfire policy or supporting more sustainable forestry endeavors, making location decisions on the outliers isn’t the way to go.

It’s human nature to evaluate risk based on the exceptional events that stick in your mind. But, evaluating your risk of wildfire is tricky. It’s not as simple to just avoid previous hotspots. The frequency and severity of wildfires will increase in a future shaped by climate change, but models and data will clarify expectations and inform better decision making. That’s what we’re doing at ClimateCheck.com: providing localized risk information on hazards linked to climate change. We give you a free way to assess current and future risk of wildfire and other hazards for every address in the US.

Let’s Talk About Wildfire Risk

Wildfire is mostly an issue in the western states. While the eastern states experience more lightning, the conifers of the northwestern forests and the chaparral of the Southwest are dryer fuel sources than the deciduous forests of the East. Add in the greater risk of drought in the West versus the increasing risk of extreme storm events and heavy precipitation in the East, subtract the vast swaths of irrigated and heavily managed agricultural land in between and there you go: wildfire is western.

Scientists, including ClimateCheck advisor John Abatzoglou, expect severe wildfires to become more common in the future due to climate change. Climate change is raising temperatures, lowering air moisture, and increasing the probability of droughts. Droughts dry out larger vegetation like trees and shrubs. Unfortunately, climate change will also bring greater volatility in precipitation, so heavy rains can lead to lots of spring grass. Add a summer of record-high temperatures and by fall that grass is kindling to ignite that larger dry vegetation: a situation perfect for wildfires.

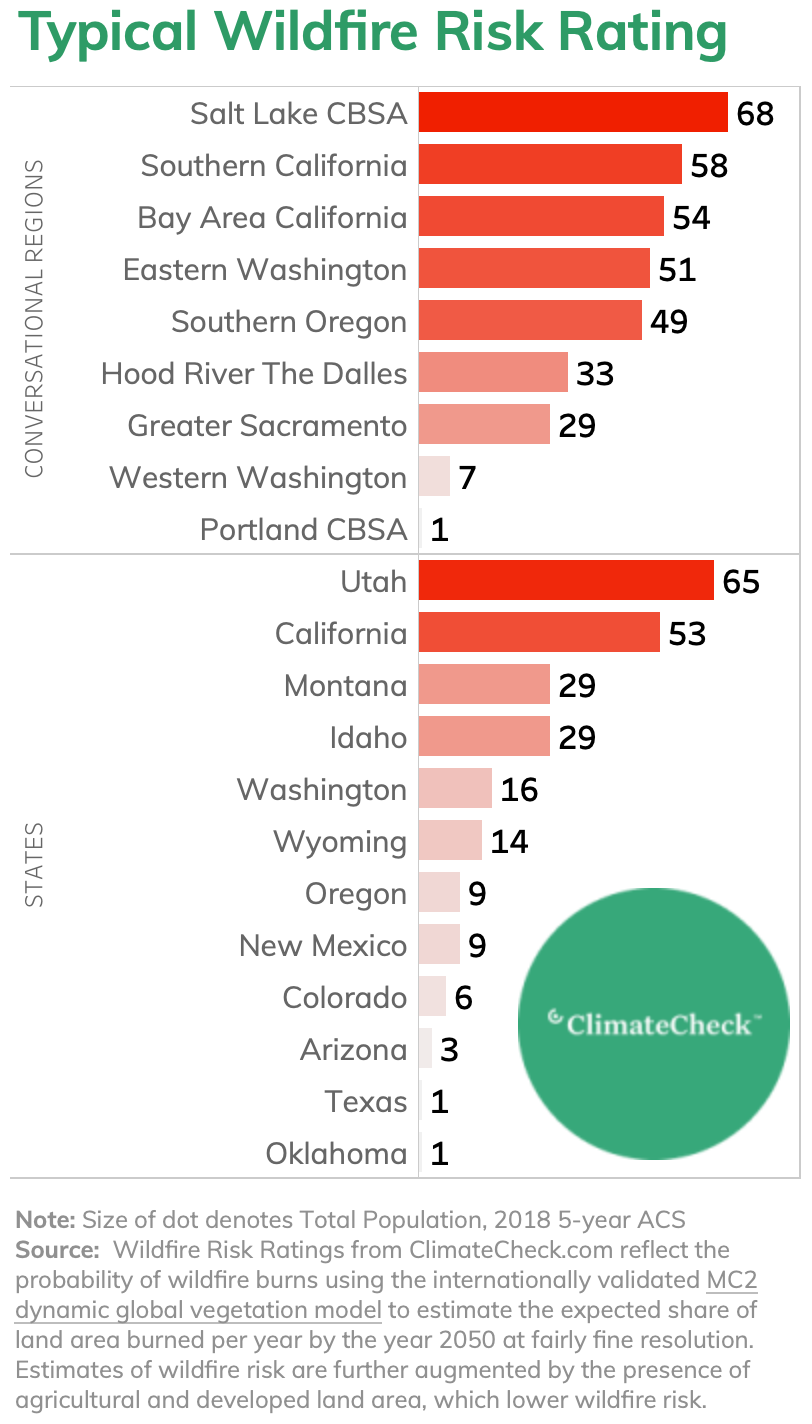

Regional Wildfire Risk

While California gets all the attention, Utah, specifically the Salt Lake City metro area, is where the typical resident has the highest probability of experiencing a wildfire in the future. The typical ClimateCheck Wildfire Risk Rating for Utah and Salt Lake City is high, with a range from 65–70 thanks to the area’s grasslands, alpine forests, and dry high desert. However, California does deserve the attention it gets thanks to the southern part of the state, where the typical Wildfire Risk Rating is 58, indicating residents frequently contend with fires.

The I-5 corridor of Washington and Oregon, the site of unusual blazes this year, mostly has low probabilities of wildfire (and high Risk Ratings for heavy precipitation). However, some fires in 2020 were severe enough to begin in nearby areas and spread into previously low-risk areas.

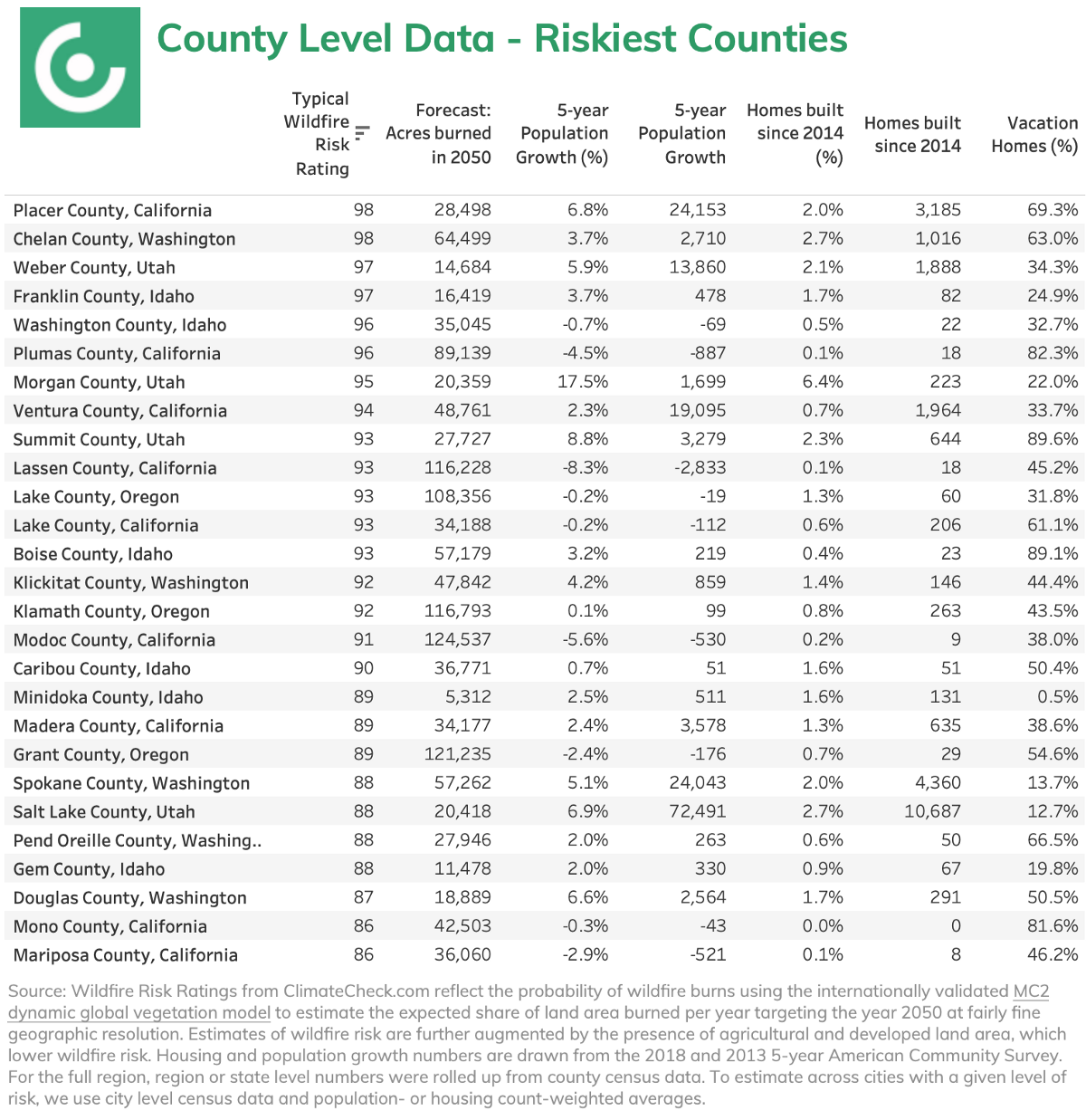

In general, the more remote the area — like forests or dry canyons — the greater the risk of wildfire. More developed areas without vegetation don’t have the fuel to burn, but the more the wildland-urban interface is blurred, the more likely housing is to be in the midst of wildfire risk. Placer County, CA, stretching from Sacramento’s suburbs to the wooded outskirts of Lake Tahoe, is tied for highest wildfire risk of US counties with the typical home there logging a wildfire risk score of 98 out of 100 and projected to burn 28,498 acres a year by 2050.

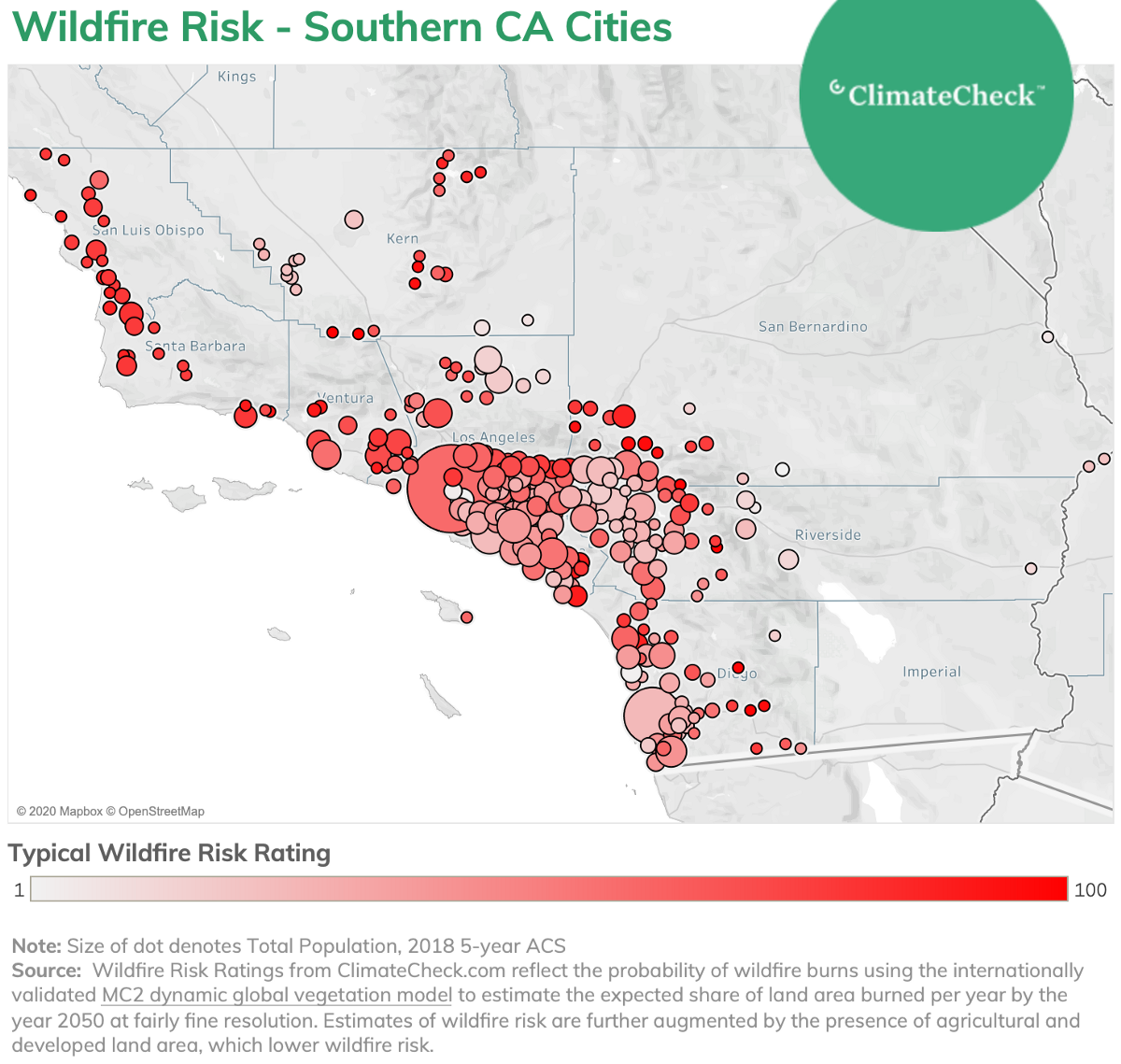

Wildfire risk can varies substantially within a county according to local features and microclimates. Take Orange County for an example. Wildfire risk ranges significantly from San Clemente, where the typical ClimateCheck Wildfire Risk Rating is 89, compared to nearby Laguna Beach, where the typical risk level is only 22.

Salt Lake City is an interesting exception to the usual pattern of greater risk away from the core. Both cities and suburbs are at risk. Weber, Morgan, and Salt Lake counties are all projected to burn more than 55,000 acres collectively each year by 2050. Weber County has a Wildfire Risk Rating of 97, similar to Morgan County’s 95, and Salt Lake County’s 96.

As the science capturing wildfire risk develops, so too will our understanding of what this means for individual and collective decision making. For example, folks in Salt Lake City may have to frequently contend with the presence of wildfires; but, like the Southern California experience, increasing fires may be smaller and property damage mitigated with homeowner and community action

Population and Housing Growth in High Wildfire Risk Areas

As exceptional wildfires rage, even in areas burned only a few years before, questions about whether or not folks should live in such high-risk communities start to rise. Using the historic experience of flooding as a case study, it’s clear that one of the major mechanisms to moderate building or buyer behavior in disaster situations is the price and availability of property insurance.

Applying or renewing for homeowners insurance is an abrupt, costly way for a homeowner to learn about their wildfire risk. Affordability, demographic pressures, lifestyle changes, and second home purchases are driving communities into the urban-wildland interface and builders are responding. Thousands of new homes and significant population growth is happening in risky wildfire areas. The population deserves to be informed about their current and future risk of wildfire.

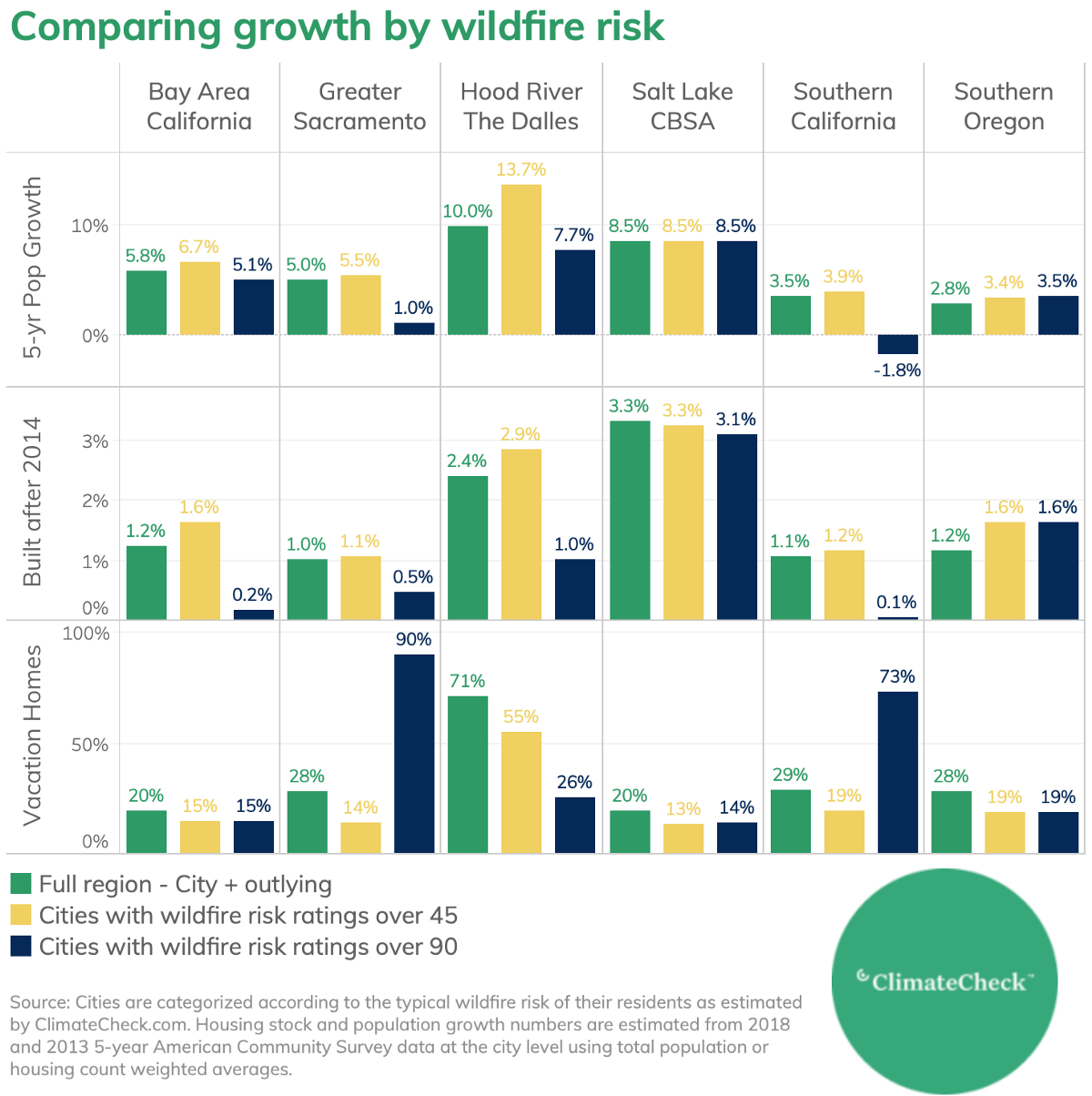

The riskiest county, Placer, County CA, saw population growth of 7 percent and added over 3 thousand new homes in recent years. A fast growing affordable job center, Salt Lake County, total population grew 6.9 percent in five years and added almost 11,000 homes since 2014 despite clocking in with a typical Wildfire Risk Rating of 88. While the US population grew 3.6 percent over the same time period, that growth has been concentrating in a smaller number of counties. Only half of US counties had positive population growth from 2013 to 2018. Only 15 percent of US counties had a population growth above 4.6 percent. While it’s not true that riskier areas are growing faster than non-risky areas, it is certainly no difficulty finding examples of significant growth where high degrees of wildfire risk are present.

This push into the wildland-urban interface during the affordability challenges of the previous decade is reflected in the consistently higher population growth and share of new construction in cities with moderate-to-high wildfire risk (typical Risk Ratings over 45) compared to their parent regions as a whole. Conversely, population growth and development in very risky cities (typical Risk Ratings over 90) is generally much lower than in the full regions they’re a part of, though Southern Oregon and the Salt Lake CBSA are exceptions. But it’s optimistic to think that low growth in the riskiest of cities is due to the appropriate consideration of wildfire risk into the home buying and building decisions. What is more likely for most of these regions is that the distance of the riskiest cities from the job core mitigates the development pressure.

The ability to move further from the urban core with remote work introduces a new variable for the location of future population growth. Will these 5-year population growth numbers from 2018, the most recent year available, hold in a more location-flexible world, or will the remote and fire-prone small towns and vacation villages experience a boom? Hopefully the regional conversations about wildfire risk — conversations that ClimateCheck hopes to be a part of — will lead to smarter growth to balance the opportunity for remote work against the environmental benefits of building more densely and sustainably closer to urban cores.

Estimating Wildfire Risk Under Climate Change

Wildfire is different from other hazards impacted by climate change. There’s the randomness of the ignition event: accidents like downed power lines, negligent or criminal human behavior, or the strike of lightning. Then there’s the confluence of complicated natural systems.

Truly massive wildfires, like the August Complex fire in California, require an exceptional confluence of historically anomalous weather patterns. It’s not just record heat, a long period of drought unquenched by more erratic precipitation, and strong off-shore winds. All of those patterns are required to overcome areas with stellar wildfire management and a history of controlled burns. Climate change drives the increasing prevalence of anomalous weather patterns. More extreme weather means more opportunity for fires — historically a natural part of the landscape — to grow into especial blazes.

Global climate models capturing significant drivers of wildfire risk are available and can be reasonably localized to U.S. conditions. Climate Check Wildfire Risk Ratings are based on projections for the proportion of land area expected to burn in a given year. The underlying data come from the MC2 dynamic global vegetation model, which uses information from an ensemble of internationally validated and curated climate models capturing changing temperatures, precipitation, and atmospheric CO2 to model the interaction of these complex meteorological and climatological systems with vegetation. MC2 models the feedback loops between systems (less vegetation means less evaporation and temperatures rise even faster) and the competition among plants for light, nitrogen, and soil water to project vegetation coverage into the future. This projected vegetation coverage is translated into an expected proportion of the surrounding area likely to burn at a relatively fine geographic granularity. The models underlying ClimateCheck’s projections of fire risk have a resolution of 4.17 km2 (1.61 mi2).

To improve data quality, estimates are supplemented with data on previous fires from the Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity project, and state-specific data where possible. Because the presence of agriculture and densely built environments lowers the local risk of wildfire, we lower the risk rating in these areas significantly using land cover databases.

At ClimateCheck, we welcome the challenge to continue providing climate science and economic risk information as it evolves and as we incorporate it into our product. Stay tuned.

¹ ClimateCheck’s wildfire Risk Rating is driven by a vegetation model that incorporates internationally validated future climate modeling to predict the share of the local land area expected to burn on average each year into the future. We target 2050 here — a time period within the span of a 30-year mortgage signed today. The Wildfire Risk Rating is a relative representation of this risk comparing a region to all others in the likelihood of a burn. To estimate the typical risk within a region (city, county, colloquial region) we weigh the Wildfire Risk Rating of individual cells (think pixels in a picture) by the population of that cell to create a population weighted measure of wildfire risk for a given geography. See below for a detailed methodology.

² Ongoing work at Climate Check involves incorporating not just the probability of a burn occurring, but the severity of the blaze. This should impact how we represent risk in Western PNW.

³ Population growth is estimated from 2013 and 2018 5-year American Community Surveys (ACS). The number of new homes is approximated with the count of homes built since 2014 as reported by the 2018 5-year ACS.