Water Rights, Water Scarcity and Climate Change

Changes to the quality and quantity of water can each have a major impact on human health and enjoyment and vulnerable economic sectors. Agriculture and urban industries such as housing thus have a huge stake in how water from natural systems gets distributed and regulated. When there’s not enough to go around, water rights can help resolve those competing uses. But water rights are complicated, steeped in legal stories that go back to the founding of each of the fifty states. Today, each state has unique laws applied to unique circumstances. This article explains the general features of those water rights systems and specifically how climate change is impacting and will continue to impact how water gets allocated.

Climate change poses several impacts to natural water systems and how people use them. Most of the world will experience changes in precipitation patterns; the amount, timing, and form (rain vs. snow) of precipitation. Hotter temperatures are also important as they decrease storage in water systems through increased evaporation. Furthermore, heat increases demand-side pressure on those systems as plants, people, power generation and other industries all require more water to function.

There will be other impacts too, but combined, these changes point to an insidious combination of decreasing water supplies and increasing demands (which of course also respond to changes in population, affluence and technology). This “water scarcity” — a term and an indicator that puts demand in relation to supply for a given region — points to a need for wise management and allocation of water across competing users, including municipal, agricultural, or industrial (including power generation).

How do Water Rights Work?

Water plays a critical role in American life and agriculture. When building or buying property, it is important to pay attention to where your water access will come from. Options include connections to public water systems, or a personal well. Water access can greatly affect the utility and value of a property; losing water access can cause significant damage.

Water rights refer to the legal right for using, selling, or diverting water. They authorize an entity, such as a property owner, a government agency, or a private company, to utilize surface water or groundwater from a specific source. The laws governing water rights vary by state, but they fall into two main doctrines: riparian rights and prior appropriation rights. Most water rights are based on the principle that entities have the right of “reasonable use” of a watercourse.

The federal government acts to control water quality through legislation such as the Clean Water Act. The federal government also sets aside land for national parks, forests, and Native American reservations; this is called reserved water rights. The water on these pieces of land can be used for limited purposes, as defined by the Federal Government. But in most cases, it falls to the states to impose regulations on the allocation of water rights for watercourses, groundwater reserves, and surface water.

Surface Water Rights

States typically follow one of two water rights doctrines for surface water rights, or a combination between the two types:

Riparian Doctrine: Landowners have the legal right to use a watercourse (such as a river or lake) that touches their land. In many cases, riparian states have moved towards using a permitting system, called the “regulated riparian” system, which imposes more regulation on water use than the original version.

- Water Rights: Rights are of equal value between landowners. A riparian right automatically resides with the property, whether it is used or not. These rights are gained by owning the land bordering a watercourse (surface water).

- Amount: The water acquisition amount is not specified, but applies to all of the water that can be “reasonably” used for that land, as long as it does not interfere with the reasonable use of a property that borders the same watercourse downstream. Reasonable use usually includes agriculture, industry, and domestic needs.

- Water Shortage Rules: All entities with water rights share the burden of the shortage, despite the amount they have previously extracted or the length of their claim.

Prior Appropriation Doctrine: (“First-in-time, first in right”) Rights are allocated based on the timing, the place, and the purpose of the water use. This doctrine dates back to the settling of the west, which required water rules for cases where land did not border a watercourse.

- Water Rights: Those that claimed the water right first have priority over those that came at later dates. The rights to water use can be lost due to non-use or abandonment, and they can usually be bought and sold.

- Amount: Entities have the right to divert water from its source for a “beneficial use” if it is available. Beneficial use refers to an amount of water that is reasonable and non-wasteful.

- Water Shortage Rules: “Junior” rights holders, those that have more recent claims to the water use, are cut off first until there is enough water for those that remain, the more “senior” rights holders.

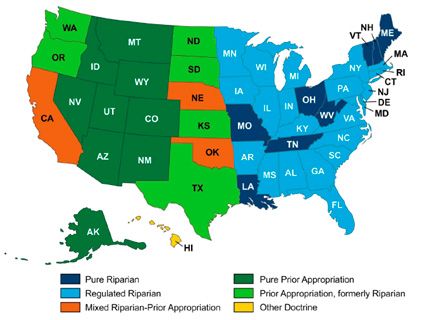

The use of doctrines is defined by geographic and historical differences. Most Western states use the prior appropriation doctrine, while most eastern states follow the riparian doctrine. Riparian doctrine lends itself better to landscapes that have plenty of water resources. In contrast, prior appropriation dates back to the development of mining rights along the Western coast. Miners needed to establish a system of water rights that could allow extraction of water when land was not directly adjacent to a watercourse.

Source: U.S. Department of Energy. 2014.

In some cases, a hybrid (or dual) doctrine is used that recognizes both types of water rights, or a mixture of the two. Oklahoma, California, and Nebraska all have hybrid rights. This can be useful for states that have a varied climate, where water is widely available in certain regions but limited in others.

Groundwater Rights & Surface Water Rights

Regulation often varies between surface water and groundwater. Groundwater is water that is extracted from below the ground, such as well water. Multiple legal doctrines are used to regulate groundwater rights including: Absolute Dominion Rule, Correlative Rights Doctrine, Prior Appropriation Doctrine, Reasonable Use Doctrine, and Restatement (Second) of Torts Rule. Most are based on the principle that each owner is allowed the “reasonable use” of the resources below their property. For more information, see this full explanation of water rights law.

Another set of water rights rules applies to surface water, such as rainwater or melting snow. Simply put, property owners have the right to any surface water on their property. But, surface water rights are more likely to be an issue when heavy rain and flash flooding cause a build-up in surface water. Correctly managing and redirecting water that lands within property from rainstorms is often the legal duty of the resident. The water rules that govern this include: Natural Flow Rule, Common Enemy Rule, and Reasonable Use Rule. This can be a problem if there are drainage problems or gutter issues; maintaining these systems is important for storm mitigation.

Urban/Public Water Use

Urban water is water that is used for drinking, household uses, landscaping, car washing, business uses, and industrial uses. Of all urban water use, most homes and businesses get water through government or privately-run facilities. Public water supply systems draw water out of surface and groundwater sources and deliver it to buildings. Over 148,000 EPA-regulated drinking water systems supply 90 percent of Americans.

Water belonging to the state is for public use, so any water extraction needs to have a water right, including extraction for public use. The rights for distributing water in cities are held by providers, which can be cities, companies, or special districts. A special district is a local government agency that serves a single purpose such as water, fire, flood, wastewater, health, transportation, or other services. They operate as not-for-profit entities with an elected board of directors.

Climate Change and Water Rights

Climate change is having a harmful impact on global water access. Rising temperatures have affected precipitation patterns and induced damaging droughts. On the other hand, climate change has also led to an increase of extreme rain and storm events, where more water falls than the soil and vegetation can absorb. Floods and extreme rain can pick up contaminants and fertilizer runoff before water drains back into waterways, harming the environment and limiting access to fresh, unpolluted water.

Water laws have evolved in the past to keep up with changes in availability and uses of water. With the onset of severe climate change-induced drought, pressure is growing to figure out better and more equitable means of water management. Changes are happening most quickly at the state level, within the Western and Southwest U.S. where drought conditions have been particularly bad in recent decades.

- The Colorado River Compact of 1922 divided the river into the Upper Basin (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming) and the Lower Basin (Arizona, California, and Nevada). Annual water allocations for each state were established based on the Compact. But decades of drought have put a strain on use of this resource. This caused the Lower Basin States to make an agreement in 2021 to significantly limit water use. Many think that the whole Compact needs to be updated to meet the new reality of climate change.

- In California, the State Water Resources Control Board is a key decision-maker for the use of water resources. In 2014, California passed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), which helps protect groundwater resources from overexploitation in the long-term. They have also imposed emergency water conservation regulation and other aggressive actions to curb water use. But critics oppose the state for taking a severe approach to urban water use without addressing the problem of agricultural water use.

Conclusion

Water rights are a crucial part of how climate-related water scarcity will have an impact on our daily lives. In areas experiencing frequent droughts, such as the western U. S., required seasonal water cutbacks are likely to become a frequent experience. Depending on the historical legacy of your state of residency, the content of the doctrine governing your water can vary between riparian and prior appropriation systems. Worsening climate conditions, bigger populations, and growing industrial needs for water may yet cause significant changes to the legal system governing water rights.