WashingtonTop Climate Change Risks: Precipitation, Heat

Risk Snapshot

Climate Change Hazard Ratings for Washington, DC

Ratings represent risk relative to North America. 100 is the highest risk for the hazard and 1 is the lowest, but does not indicate no risk. Flood and fire are rated based on the buildings in Washington exposed to these hazards. See hazard sections below and check your address for details.

Get an Instant Risk Assessment

People in Washington, DC are especially likely to experience increased risks from precipitation and heat.

Precipitation and heat risk in Washington, DC is extreme. Drought risk is significant. About 63% of buildings in Washington, DC are at risk of wildfire, and the risk level for these buildings is relatively low. About 11% of buildings in Washington, DC are at risk of flooding, and the risk level for these buildings is significant.

Precipitation risk in Washington, DC

The share of precipitation during the biggest downpours in Washington is projected to increase.

A downpour for Washington, DC is a two-day rainfall total over 0.9 inches. Around 1990, about 41.0% of precipitation fell during these downpours. In 2050, this is projected to be about 45.0%. The annual precipitation in Washington, DC is projected to increase from about 42.2" to about 45.4".

Heat risk in Washington, DC

The number of the hottest days in Washington is projected to keep increasing.

In a typical year around 1990, people in Washington, DC experienced about 7 days above 94.6ºF in a year. By 2050, people in Washington are projected to experience an average of about 38 days per year over 94.6ºF.

Fire risk in Washington, DC

The risk on the most dangerous fire weather days in Washington is low. The number of these days per year is expected to increase through 2050.

Of 309 census tracts in Washington, DC, there are 193 where more than a quarter of buildings have significant fire risk, and 169 where more than half of buildings have significant fire risk. Property owners can take steps to mitigate their risks from wildfires.

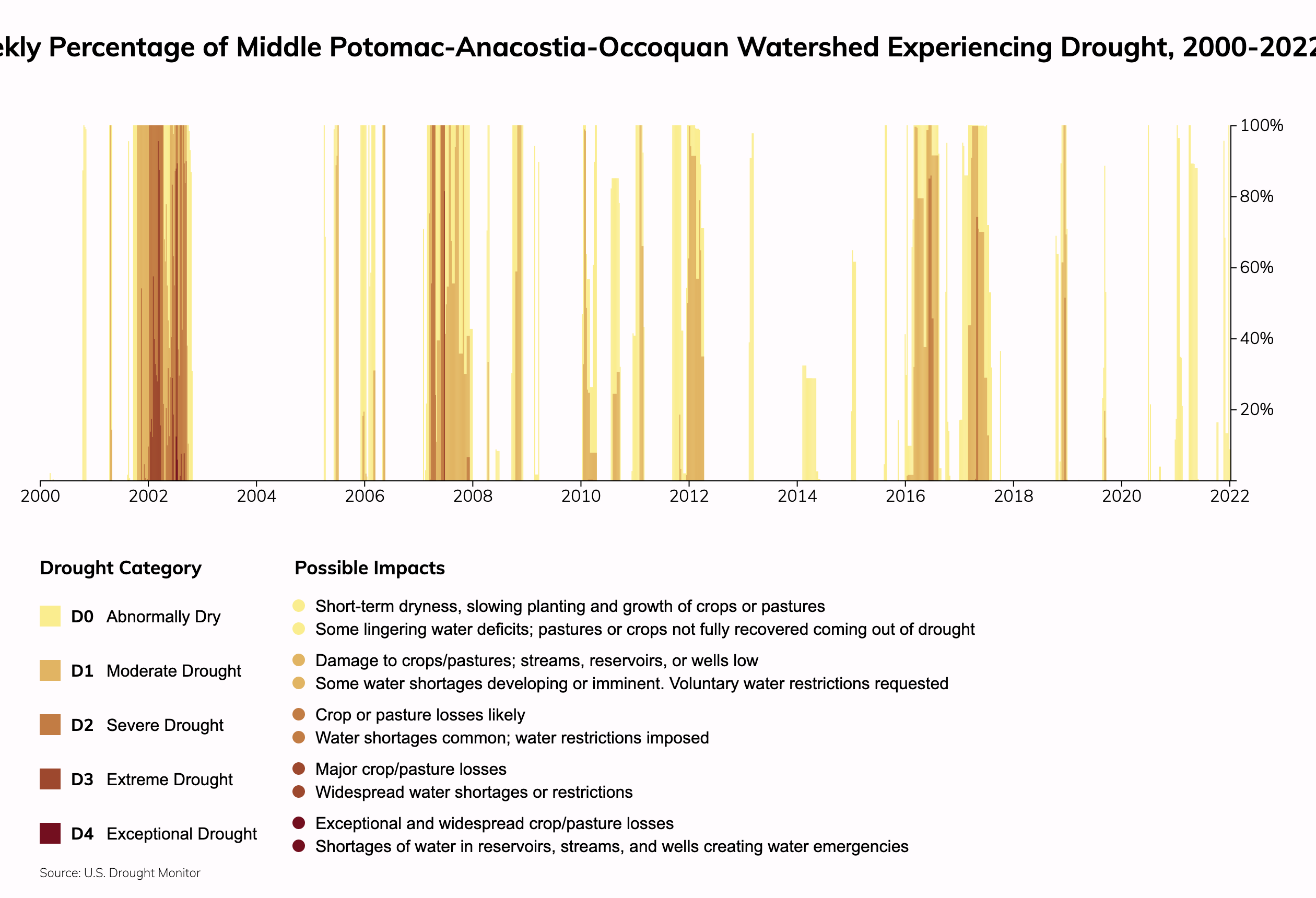

Drought risk in Washington, DC

The average water stress in Washington is projected to be about the same around 2050 as around 2015.

The Middle Potomac-Anacostia-Occoquan watershed, which contains Washington, DC, has experienced 400 weeks (33% of weeks) since 2000 with some of its area in drought of any level, and 21 weeks (2% of weeks) since 2000 with some of its area in Extreme or Exceptional drought. Source: National Drought Monitor.

Flood risk in Washington, DC

Buildings at risk in Washington average about a 29% chance of a flood about 10.0 inches deep over 30 years.

Of 309 census tracts in Washington, DC, there are 31 where more than half of buildings have significant risk from storm surge, high tide flooding, surface (pluvial) flooding, and riverine (fluvial) flooding. Property owners can check a specific address for flood risk including FEMA flood zone, then take steps to reduce their vulnerability to flooding damage.

How can we limit climate change and live in a transforming world?

The projections on this page describe a future that we still have a chance to avoid. To keep average global warming below 1.5ºC—the goal agreed on in the 2015 Paris Climate Accords—we need to act rapidly to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Understand Risks

The risks presented on this page reflect modeled averages for Washington, DC under one projected emissions scenario and can vary for individual properties. To find out more, check a specific address and request a report describing risks to your property and in your area.

Reduce Emissions

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report states: “If global emissions continue at current rates, the remaining carbon budget for keeping warming to 1.5ºC will likely be exhausted before 2030.” This remaining carbon budget is about the same amount as total global emissions 2010-2019.

Protect Homes and Communities

Check our free report for tips on protecting your home from hazards.